Invisible Children (Participation)

A lot of people are talking about Invisible Children Video. You can watch below and also read the below articles that push complexity about this campaign

We got trouble.

For those asking what you can do to help, please link to visiblechildren.tumblr.com wherever you see KONY 2012 posts. And tweet a link to this page to famous people on Twitter who are talking about KONY 2012!

I do not doubt for a second that those involved in KONY 2012 have great intentions, nor do I doubt for a second that Joseph Kony is a very evil man. But despite this, I’m strongly opposed to the KONY 2012 campaign.

KONY 2012 is the product of a group called Invisible Children, a controversial activist group and not-for-profit. They’ve released 11 films, most with an accompanying bracelet colour (KONY 2012 is fittingly red), all of which focus on Joseph Kony. When we buy merch from them, when we link to their video, when we put up posters linking to their website, we support the organization. I don’t think that’s a good thing, and I’m not alone.

Invisible Children has been condemned time and time again. As a registered not-for-profit, its finances are public. Last year, the organization spent $8,676,614. Only 32% went to direct services (page 6), with much of the rest going to staff salaries, travel and transport, and film production. This is far from ideal for an issue which arguably needs action and aid, not awareness, and Charity Navigator rates their accountability 2/4 stars because they lack an external audit committee. But it goes way deeper than that.

The group is in favour of direct military intervention, and their money supports the Ugandan government’s army and various other military forces. Here’s a photo of the founders of Invisible Children posing with weapons and personnel of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army. Both the Ugandan army and Sudan People’s Liberation Army are riddled with accusations of rape and looting, but Invisible Children defends them, arguing that the Ugandan army is “better equipped than that of any of the other affected countries”, although Kony is no longer active in Uganda and hasn’t been since 2006 by their own admission. These books each refer to the rape and sexual assault that are perennial issues with the UPDF, the military group Invisible Children is defending.

Still, the bulk of Invisible Children’s spending isn’t on supporting African militias, but on awareness and filmmaking. Which can be great, except that Foreign Affairs has claimed that Invisible Children (among others) “manipulates facts for strategic purposes, exaggerating the scale of LRA abductions and murders and emphasizing the LRA’s use of innocent children as soldiers, and portraying Kony — a brutal man, to be sure — as uniquely awful, a Kurtz-like embodiment of evil.” He’s certainly evil, but exaggeration and manipulation to capture the public eye is unproductive, unprofessional and dishonest.

As Chris Blattman, a political scientist at Yale, writes on the topic of IC’s programming, “There’s also something inherently misleading, naive, maybe even dangerous, about the idea of rescuing children or saving of Africa. […] It hints uncomfortably of the White Man’s Burden. Worse, sometimes it does more than hint. The savior attitude is pervasive in advocacy, and it inevitably shapes programming. Usually misconceived programming.”

Still, Kony’s a bad guy, and he’s been around a while. Which is why the US has been involved in stopping him for years. U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) has sent multiple missions to capture or kill Kony over the years. And they’ve failed time and time again, each provoking a ferocious response and increased retaliative slaughter. The issue with taking out a man who uses a child army is that his bodyguards are children. Any effort to capture or kill him will almost certainly result in many children’s deaths, an impact that needs to be minimized as much as possible. Each attempt brings more retaliation. And yet Invisible Children supports military intervention. Kony has been involved in peace talks in the past, which have fallen through. But Invisible Children is now focusing on military intervention.

Military intervention may or may not be the right idea, but people supporting KONY 2012 probably don’t realize they’re supporting the Ugandan military who are themselves raping and looting away. If people know this and still support Invisible Children because they feel it’s the best solution based on their knowledge and research, I have no issue with that. But I don’t think most people are in that position, and that’s a problem.

Is awareness good? Yes. But these problems are highly complex, not one-dimensional and, frankly, aren’t of the nature that can be solved by postering, film-making and changing your Facebook profile picture, as hard as that is to swallow. Giving your money and public support to Invisible Children so they can spend it on supporting ill-advised violent intervention and movie #12 isn’t helping. Do I have a better answer? No, I don’t, but that doesn’t mean that you should support KONY 2012 just because it’s something. Something isn’t always better than nothing. Sometimes it’s worse.

If you want to write to your Member of Parliament or your Senator or the President or the Prime Minister, by all means, go ahead. If you want to post about Joseph Kony’s crimes on Facebook, go ahead. But let’s keep it about Joseph Kony, not KONY 2012.

~ Grant Oyston, visiblechildren@grantoyston.com

Grant Oyston is a sociology and political science student at Acadia University in Nova Scotia, Canada. You can help spread the word about this by linking to his blog at visiblechildren.tumblr.com anywhere you see posts about KONY 2012.

Taking ‘Kony 2012′ Down A Notch

The makers of Kony 2012. Makes sense. (Photo: Glenna Gordon / Scarlett Lion)

As we speak, one of the most pervasive and successful human rights based viral campaigns in recent memory is underway. Invisible Children’s ‘Kony 2012‘ campaign has taken Twitter, Youtube, Facebook and every other mainstream social media refuge by storm. In many ways, it is quite impressive. But there’s one glaring problem: the campaign reflects neither the realities of northern Ugandan nor the attitudes of its people. In this context, this post examines the explicit and implicit claims made by the ‘Kony 2012′ campaign and tests them against the empirical record on the ground.

Before jumping into the fray, however, I should preface the post by noting that, in many ways, Invisible Children have done a fantastic job in advocating for the rights of northern Ugandans, highlighting the conflict and providing tangible benefits to victims and survivors of LRA brutality. Indeed, this post is not intended to take aim at Invisible Children as an organization but rather to debunk some of the myths its ‘Kony 2012′ campaign is propagating.

The Problem is Popularity?

Kony 2012 is about making Joseph Kony, the leader of the notorious LRA, famous because, the line of reasoning goes, if everyone knew him, no one would be able to stand idly by as he waged his brutal campaign of terror against the people of East Africa.

I am actually stupefied that any analysis of the ‘LRA question’ results in the identification of the problem being that “Kony isn’t popular enough”. The reality is that few don’t know who Joseph Kony is in East Africa and the Great Lakes Region, making it all-too-apparent that this isn’t about them, their views or their experiences. But even more puzzling is that Joseph Kony is one of the best known alleged war criminals in the world – including in the United States. This is the case in large part because of the advocacy of Western NGOs, including Invisible Children and the Enough Project as well as the ICC arrest warrants issued against Kony and his senior command.

I would understand if this were the 1990s or even the early 2000s when the misery plaguing northern Uganda flew completely under the radar. I would understand if this campaign was about the ongoing conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo. But a campaign in 2012, premised on Joseph Kony not being famous enough is just folly.

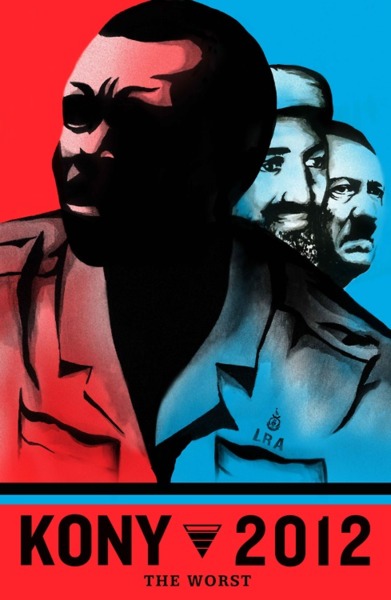

A poster from the ‘Kony 2012’ campaign.

Umm…what about northern Ugandans?

It is hard to respect any documentary on northern Uganda where a five year-old white boy features more prominently than any northern Ugandan victim or survivor. Incredibly, with the exception of the adolescent northern Ugandan victim, Jacob, the voices of northern Ugandans go almost completely unheard.

It isn’t hard to imagine why the views of northern Ugandans wouldn’t be considered: they don’t fit with the narrative produced and reproduced in the insulated echo chamber that produced the ‘Kony 2012′ film.

‘Kony 2012′, quite dubiously, avoids stepping into the ‘peace-justice’ question in northern Uganda precisely because it is a world of contesting and plural views, eloquently expressed by the northern Ugandans themselves. Some reports suggest that the majority of Acholi people continue to support the amnesty process whereby LRA combatants – including senior officials – return to the country in exchange for amnesty and entering a process of ‘traditional justice’. Many continue to support the Ugandan Amnesty law because of the reality that it is their own children who constitute the LRA. Once again, this issue is barely touched upon in the film. Yet the LRA poses a stark dilemma to the people of northern Uganda: it is now composed primarily of child soldiers, most of whom were abducted and forced to join the rebel ranks and commit atrocities. Labeling them “victims” or “perpetrators” becomes particularly problematic as they are often both.

Furthermore, the crisis in northern Ugandan is not seen by its citizens as one that is the result of the LRA. Yes, you read that right. The conflict in the region is viewed as one wherein both the Government of Uganda and the LRA, as well as their regional supporters (primarily South Sudan and Khartoum, respectively) have perpetrated and benefited from nearly twenty-five years of systemic and structural violence and displacement. This pattern is what Chris Dolan has eloquently and persuasively termed ‘social torture‘ wherein both the Ugandan Government and the LRA’s treatment of the population has resulted in symptoms of collective torture and the blurring of the perpetrator-victim binary.

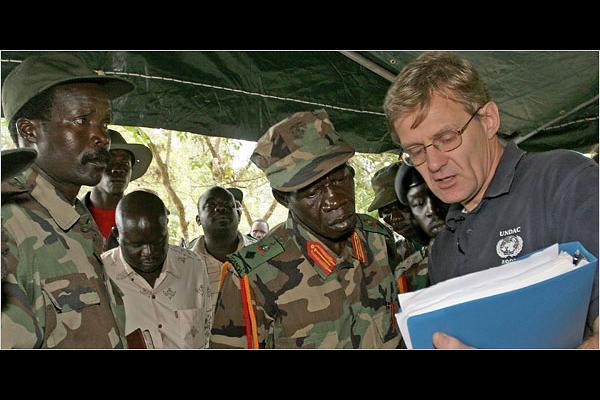

Kony and his former second in command, Vincent Otti, with former UN Undersecretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, Jan Egeland (Photo: New York Times)

The Solution?

Given Invisible Children’s problematic identification of the issue, it becomes impossible for them to come up with an appropriate vision of resolving the crisis.

Invisible Children is, perhaps rightly, proud that it put the ‘LRA question’ on the Obama administration’s agenda. In this context, last year’s announcement that the administration would send 100 military ‘advisors’ to Uganda was widely celebrated. But this triumphalism occludes key realities.

The sending of 100 troops was not, in any sense, an altruistic move by the administration. First, it went unreported that many of the troops were already in Uganda. Second, the announcement was, at least in part, a tit-for-tat response for the Government of Uganda’s military engagement in Somalia – where the US refuses to deploy troops. As Matt Brown of the Enough Project conceded:

“The U.S. doesn’t have to fight al-Qaida-linked Shabab in Somalia, so we help Uganda take care of their domestic security problems, freeing them up to fight a more dangerous – or a more pressing, perhaps – issue in Somalia.

It is clear that the ‘Kony 2012′ campaign sees the 100 US troop allotment as inadequate. Here they are right – 100 US troops is not the solution. But their own answer is highly problematic.

We know what the makers of “Kony 2012″ believe should happen but they won’t say it explicitly, except to say that Kony must be “stopped”.

Obama’s orders for his 100 troops – presumably supported by those behind ‘Kony 2012′ – is to “kill or capture” Joseph Kony. I don’t think it is a stretch to suggest that many of the same individuals who will form the legion of participants in ‘Kony 2012′ were on the streets celebrating the killing of Osama bin Laden. It thus likely holds that they bought into the belief, proffered by Obama himself, that bin Laden’s killing amounted to justice and if you didn’t agree, you should get your head checked.

The solution then, is something similar: an American-led intervention into at least four countries where the LRA is or has been active (Uganda, the DRC, the Central African Republic and South Sudan) to hunt down Kony. Capturing him, after all, is secondary to “stopping” him.

The idea of “stopping Kony”, of course plays into the narrative created by the ‘Kony 2012′ campaign where what actually happens to Kony and the LRA is irrelevant. The unspecific aim of “stopping” him is sufficient. Who, after all, doesn’t want Kony “stopped”? But then what? If Kony is killed or captured, then what? What happens to the other members of the LRA? ‘Kony 2012′ offers no answers here.

In this context, it is worthwhile remembering that massive regional military solutions (Operations Iron Fist and Lightning Thunder most recently), with support from the US, have thus far failed to dismantle or “stop” the LRA. These failures have created serious and legitimate doubts that the ‘LRA question’ is one that can be resolved by military means.

Incredibly, there is no mention in the film or the campaign that northern Ugandans are currently enjoying the longest period of peace since the conflict began in 1986. Virtually every single northern Ugandan I spoke to during my own field research believes that there is peace in the region. While sporadic violence continues, particularly as a result of bitter land disputes, there have been no LRA attacks in years. In the mid 2000s, the ‘LRA problem’ was exported out of Uganda. The LRA is currently residing in the DRC, CAR, and perhaps parts of South Sudan and even Darfur. Today, land issues and the recent Walk to Work crisis are higher on the agenda than the LRA in northern Uganda.

Lastly, killing Kony cannot resolve the actual sources of the crisis which are far more structural than superficial (to put it lightly) analyses like ‘Kony 2012′ would like to admit. As respected scholars of northern Uganda, Mareike Schomerus, Tim Allen, and Koen Vlassenroot, recently argued,

“Until the underlying problem — the region’s poor governance — is adequately dealt with, there will be no sustainable peace.”

Kony (left) with Otti.

The Need for a Sober Second Thought

In the end, ‘Kony 2012′ falls prey to the obfuscating, simplified and wildly erroneous narrative of a legitimate, terror-fighting, innocent partner of the West (the Government of Uganda) seeking to eliminate a band of lunatic, child-thieving, machine-gun wielding mystics (the LRA). The main beneficiary of this narrative is, once again, the Ugandan Government of Yoweri Museveni, whose legitimacy is bolstered and – if the ‘Kony 2012′ campaign is ‘successful’ – will receive more military funding and support from the US.

Of course, as a viral campaign launched through social media, ‘Kony 2012′ is impressive, if not unprecedented. It will, undoubtedly, mobilize and morph a horde of sincere American youths into proxy war criminal hunters. It will further succeed in increasing the ‘popularity’ of Joseph Kony and the LRA in the United States. But it will do so for many of – if not all – the wrong reasons.

I remember when I was in grade school and a teacher told the students that it was actually difficult to fail. “You have to try to fail,” he said. If ‘Kony 2012′ is to be judged by its reflection of the realities on the ground in northern Uganda and how it measures up against the empirical record, the makers of Kony 2012 tried – and succeeded.

——————————

Check out this excellent account by Daniel Solomon over at his blog, Securing Rights.

Also, big thanks to my friend and colleague, Paul Kirby, for his insightful comments on a draft of this post.

Third post

Invisible Children and Joseph Kony

You may have heard of the little film titled Invisible Children that came out in 2006 documenting the Lord’s Resistance Army and their kidnappings of children. It took the media world’s attention and ran with it, generating millions of dollars for their newly formed NGO, Invisible Children.The aim was to shine a spotlight on the atrocities, to bring people’s attention to what was happening – hence the title, Invisible Children. They were going to make these children visible.

I became aware of the film shortly after it was released as many in the Church took on the cause of raising money for Invisible Children, screening the film, etc… The filmmakers exploded onto the media and humanitarian scene, creating apparel (their store is now selling ‘action kits’), holding large events, and marketing in all corners – all ostensibly for the benefit of children in Northern Uganda, often centered around the Acholi people and even more so an area named Gulu, where the LRA leader Joseph Kony is from (I attended a church that held a ‘Gulu Walk’ mimicking the children’s flight).

Now, they’re out with a new film titled, Kony – which has again gone massively viral.The aim of the film, according to Invisible Children, is to “make Joseph Kony famous…to raise support for his arrest”.

The problem? From the beginning to now, the goal was premised on a White desire to save downtrodden Africa regardless of facts. The movies are premised on the idea that: North American (White) attention will save Africa. I wrote about this same thing in regards to Nick Kristof and the logic goes like this:

The problem? From the beginning to now, the goal was premised on a White desire to save downtrodden Africa regardless of facts. The movies are premised on the idea that: North American (White) attention will save Africa. I wrote about this same thing in regards to Nick Kristof and the logic goes like this:

White people only care about White people and the only way to save Black people is to get White people to care about them, so to save Black people we need to talk about White people.

But the problem is even bigger than this. It feeds into the public perception of what Africa is. It’s full of war, famine and rape. Its people can’t help themselves.

Kony and his atrocities are nothing new; they’ve been happening for a long time. There have been numerous very public policy discussions within North America about how best to deal with Kony but he’s elusive, he knows how to run and really governments in North America are minimally interested. To the people in the area he terrorizes, they have had conversations about how to deal with Kony & how to deal with things bigger than Kony – malaria, disease, education, society. I have an Acholi colleague who is researching education in conflict/post-conflict Acholiland. They care, they know, they’re researching and problem solving – this is nothing new, Kony is already infamous. So what will educating White people do?

Some will say, what’s the problem with bringing attention to the atrocities? This is a good thing, now people will know and do something. Who cares if it is White people, Black people, or Purple people who do it?

One problem: It falls into the trap, the belief that the problem is ignorance and the answer is education. When we tell more people about Kony and the LRA, something WILL happen. It’s not true. Bono, Bob Geldolf, Angelina Jolie and thousands of others have brought more attention, more education, more money to issues – it doesn’t solve them. White ignorance is not the problem. White colonialism/oppression/domination/violence (whatever you want to call it) in the past and present is. It is built on the idea that Africa needs saving – that it is the White man’s burden to do so. More education does not change the systems and structures of oppression, those that need Africa to be the place of suffering and war and saving.

Kony and the LRA, something WILL happen. It’s not true. Bono, Bob Geldolf, Angelina Jolie and thousands of others have brought more attention, more education, more money to issues – it doesn’t solve them. White ignorance is not the problem. White colonialism/oppression/domination/violence (whatever you want to call it) in the past and present is. It is built on the idea that Africa needs saving – that it is the White man’s burden to do so. More education does not change the systems and structures of oppression, those that need Africa to be the place of suffering and war and saving.

It’s also about history. White folk have for centuries built industries on saving Black people in Africa. In creating images of what Africans look like, in order to justify saving them. Is it any coincidence that all of the filmmakers and subsequent heads of the NGO are white? Is it any coincidence that, despite ‘partnering’ with local people, on Invisible Children’s website, in a colonial-esque era division, that the White people involved in the organization are framed in a modern, neutral (White) room in ‘hip’ fashion while the Africans all have straw huts in the background? No, the ideal African still lives in huts! They’re exotic and poor. This is all no surprise when we bring history into the picture.

It’s also about history. White folk have for centuries built industries on saving Black people in Africa. In creating images of what Africans look like, in order to justify saving them. Is it any coincidence that all of the filmmakers and subsequent heads of the NGO are white? Is it any coincidence that, despite ‘partnering’ with local people, on Invisible Children’s website, in a colonial-esque era division, that the White people involved in the organization are framed in a modern, neutral (White) room in ‘hip’ fashion while the Africans all have straw huts in the background? No, the ideal African still lives in huts! They’re exotic and poor. This is all no surprise when we bring history into the picture.

Part of this is the centering of our Western vision and logic. The very idea of ‘Invisible’ is ludicrous – these children were never invisible to their communities and families – only to us. It harkens back to the ‘unspoilt’ land of the new worlds where ‘no one had ever been before’ and which completely ignored the lives and realities of the Indigenous people, the Africans who had lived there for centuries before – who knew everything there was to know about this ‘untouched’ land. It is the re-centering of the West and the glossing over of those whose lives are being impacted most. We need to learn: It’s not about us. Race does matter for this reason, because of how it is constituted by history and continues to shape how we view the world.

There are other critiques about where the money that is raised goes, the filmmakers are just kids with no idea how to distribute aid, whether aid is really effective in solving problem, that Kony is long gone from Uganda, etc… They are all relevant but huge issues in themselves. This article is about representation and how Invisible Children erases local realities while purporting to showcase them. It’s about those people who watch the film and believe awareness is the answer to solving the problems. Raising awareness is our generations pat on the back, our absolution of guilt, our mechanism for maintaining our neo-liberal, do-good Whiteness which separates us from those OTHER horrible people who ‘do nothing’. We believe making a film or watching a film changes systems of oppression, patterns of violence, or centuries of colonial erasure. That is what this article is about.

You can read more about how the film frames “Bad guys vs. Good guys” from How Matters.

For those of faith who are supporting Invisible Children, some bigger questions to think on regarding love and charity.

I am so fascinated by this media campaign since I saw the video on Monday evening. Like many people I shared the video and made a small donation to the Invisible Children fund. Now after all these articles are surfacing that challenge the non-profit organization and its motives, I feel pretty stupid. However, I don’t necessarily buy into the idea that this is the worst thing that could happen. Yeah the non-profit spends more money on staff salaries and video production than on real charity work, but I find it pretty motivational that the movie spread so fast. Just about everyone I know on Facebook was sharing the video and it was nice to see people all caring about something that wasn’t an instagram photo of a sidewalk. Obviously the video made use of emotional appeals more than logical ones, but is that really so bad? It’s good to care about people and want to help them. It’s good to get information about the evil people in this world. The only bad thing I can see in this situation would be refusing to read information about the different sides of this discussion. I’m also looking forward to seeing what/if Invisible Children will say in response to these articles.

I don’t think it is about feeling “stupid” or the “good or bad” here but rather critically thinking about a video that has over 8 million hits in like a day. It is about thinking about the larger context and history — here are two more really interesting articles

http://www.clutchmagonline.com/2012/03/is-the-kony-2012-viral-vid-another-case-of-white-savior-syndrome/

http://afripopmag.com/2012/03/are-africans-invisible-rounding-up-the-stop-kony-campaign-debate/

As you said, Josephine, it is about where the information takes us is key

I felt as if this campaign received a ton of attention over night – and exploded into social media in an incredible way. However, this and other situations like it happen around the world in many different countries daily. I think that the campaign is well intended, but I also believe that they are going about it in an odd manor. Putting up posters in various cities will raise awareness, but will it actually get Kony captured and the situation taken care of in the way we believe is best? Highly doubtful. I do not know the motives behind the campaign, but in my observation movements that grow quickly often fade quickly and people are left wondering what they were really about. I would exercise caution when donating to a cause that is so new and is surrounded in conspiracies and mystery. It is good to want to make a difference, but there are most likely tons of other people like Kony out in the world doing very similar things, and I do not think that wasting all the paper to make posters that may not even make a difference is worth it. What makes this cause so much different than any of the others happening in the world right now? I highly doubt this is the only case revolving around these topics. I am curious as to where this movement will go – and how long it will last.

It’s incredible to see a campaign like “Kony 2012” get so much attention so quickly. I personally felt inspired by the video when I saw it on Tuesday morning. However, now that I’ve read articles about it, I do feel that the campaign is not as good as it should be. Leaving out information is not good in any campaign. However, bring awareness to this issue isn’t really a bad thing. People like knowing what is going on in the world, but I just don’t think it will really solve this issue. I do wonder how this campaign will turn out and how long it will last.

After seeing all of my friends on Facebook join the Kony 2012 bandwagon, I was interested and wanted to check it out. I watched the video last Monday night and I will admit that I was greatly impacted by the video and I wanted to donate money to help the cause. But after reading these articles, I feel less obligated to donate money now because I now feel like giving money won’t really help the people be more aware of the things going on in Uganda or make people more aware about Joseph Kony. I know that the Kony 2012 has good intention and I am really glad that the Invisible children organization is taking action to make a difference. Over all I guess I feel I confused on what to believe regarding this issue or I conflicted with whether or not I should take action or not.

Like, Meesha says, after seeng my news feed on Facebook blown up with “Kony 2012” articles and videos, I had to see what it all was about. I watched the video and was very fascinated and agreed with the people supporting. But since then I have read many articles, including this one, that rejects the founders’ of Kony 2012, and doubt has become increasingly for me. I don’t doubt this is a problem, but the things that are being done, have not shown much help. I think too much money is being poured into this campaign and everything, when we have many of our own problems here in the US that all this money could go towards. Not to mention the millions of dollars used thus far has gone more towards awareness than actually making any improvement of fixing the problem.

The LRA has been a problem for decades and I have known about it and been following the issue for many years. The reality is that most of the world is living in tyranny, either from oppressive governments or other forces, such as rebel armies. Unfortunately, there are no “good guys” in the conflict involving the LRA. The alternative to Kony is the dictatorial regimes of Uganda, the DRC, and Sudan. (Sudanese ruler Bashir is committing his own genocides, in which millions have died.)

Arms is the only way to defeat an oppressor. A tyrant will never step down peaceably. Only when he fears his own demise will he relinquish power. The U.S. should be providing no support to Uganda, the DRC, or Sudan. We could theoretically destroy the LRA in a matter of a couple of days, but what would that leave the people of East Africa? There will be a new oppressor to step in after Kony is gone. Our country must limit its military support to forces that promise freedom and democracy.